Follow the brown signs

News of a scuttling

Since moving out of the Big Smoke Bristol is now my closest city. Just voted the best UK city to live according to The Sunday Times it has the winning mix of nearby countryside, lovely houses, good schools and “buzzy” feel. Its cultural and industrial heritage is outstanding, with Banksy daubing its streets and rolling stock since the early ’90s and Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge and famous docks looking as grand and impressive as when the largest ships in the world once sailed from them, Bristolians have justifiable reason to be proud of their hometown.

When my Australian friends Ben, Kate and Annie came to stay recently they loved Bristol. I was bullied into actually crossing the suspension bridge for the first time (left, mid way through) despite my cries of vertiginous agony and we mooched around soaking up the “buzzy” atmosphere. “It feels like Melbourne here” they said and I had to agree. Appropriate really as the vibrant Aussie city has just been ranked the most livable city in the world by The Economist Intelligence Unit so they’re both clearly doing something right. For all the reasons to love it though Ben, a doctor, was most impressed that he was in the city that lends its name to a chart every medical student must memorise (and one that is stuck to the back of bathroom doors in student halls across the world), The Bristol Stool Scale (warning, graphic link!). Oh there are a lot of reasons to love this city…

When my Australian friends Ben, Kate and Annie came to stay recently they loved Bristol. I was bullied into actually crossing the suspension bridge for the first time (left, mid way through) despite my cries of vertiginous agony and we mooched around soaking up the “buzzy” atmosphere. “It feels like Melbourne here” they said and I had to agree. Appropriate really as the vibrant Aussie city has just been ranked the most livable city in the world by The Economist Intelligence Unit so they’re both clearly doing something right. For all the reasons to love it though Ben, a doctor, was most impressed that he was in the city that lends its name to a chart every medical student must memorise (and one that is stuck to the back of bathroom doors in student halls across the world), The Bristol Stool Scale (warning, graphic link!). Oh there are a lot of reasons to love this city…

With so much to do in Bristol the council have been very good at signposting all their attractions in the very best way possible, with loads of brown signs! This cacophony of brown-signage left me spoilt for choice, with a selection of science centres, community arts projects, zoo, museum, ships and aquarium I wanted to do every one but really there was only one winner… The man who quite literally changed the face of this city and indeed our modern world, Brunel and his ss Great Britain would be the first stop on my brown signed trail.

With so much to do in Bristol the council have been very good at signposting all their attractions in the very best way possible, with loads of brown signs! This cacophony of brown-signage left me spoilt for choice, with a selection of science centres, community arts projects, zoo, museum, ships and aquarium I wanted to do every one but really there was only one winner… The man who quite literally changed the face of this city and indeed our modern world, Brunel and his ss Great Britain would be the first stop on my brown signed trail.

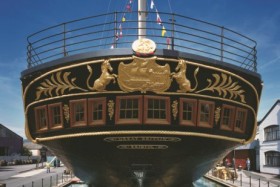

This “grand old lady” sits in the very same dock she was born in and the story of how she ended up back here exactly 127 years to the day after she left is truly amazing. The ship is now a “museum ship” which allows visitors to understand and experience her story both in the fantastic dockyard discovery centre and aboard the ship herself. The ss Great Britain Trust have gone to great lengths to ensure visitors get information and interaction at the engaging discovery centre before boarding via informative videos, timelines, stories, games and artefacts you can actually pick up and examine yourself. I felt like I really got to know her before I’d even embarked.

This “grand old lady” sits in the very same dock she was born in and the story of how she ended up back here exactly 127 years to the day after she left is truly amazing. The ship is now a “museum ship” which allows visitors to understand and experience her story both in the fantastic dockyard discovery centre and aboard the ship herself. The ss Great Britain Trust have gone to great lengths to ensure visitors get information and interaction at the engaging discovery centre before boarding via informative videos, timelines, stories, games and artefacts you can actually pick up and examine yourself. I felt like I really got to know her before I’d even embarked.

An airtight glass roof surrounds the hull of the ship. This was installed to prevent further corrosion to the iron and allows a constant 20% humidity down there. Being inside the actual dry dock where the ship was built, seeing the near vertical steps which the ship builders would have been scurrying up and down as they built her added real meaning and authenticity to the whole experience. Standing in the same places where Brunel once stood too, for me at least, was spine-tinglingly brilliant.

An airtight glass roof surrounds the hull of the ship. This was installed to prevent further corrosion to the iron and allows a constant 20% humidity down there. Being inside the actual dry dock where the ship was built, seeing the near vertical steps which the ship builders would have been scurrying up and down as they built her added real meaning and authenticity to the whole experience. Standing in the same places where Brunel once stood too, for me at least, was spine-tinglingly brilliant.

Although there are some understated reminders to “please not pick off the paintwork” there’s nothing to stop visitors walking right up and laying their hands on the huge iron hulk or running a finger over the rivets holding her together (I did, a bit too much maybe, onlookers would probably have described my stroking as a little bit creepy). The closeness of the ship without ropes or barriers in the way was great and walking alongside the hull that would have beaten through a million miles of high seas and tranquil oceans made me quite emotional, so I sat for a while sweatily appreciating her in all her glory.

Although there are some understated reminders to “please not pick off the paintwork” there’s nothing to stop visitors walking right up and laying their hands on the huge iron hulk or running a finger over the rivets holding her together (I did, a bit too much maybe, onlookers would probably have described my stroking as a little bit creepy). The closeness of the ship without ropes or barriers in the way was great and walking alongside the hull that would have beaten through a million miles of high seas and tranquil oceans made me quite emotional, so I sat for a while sweatily appreciating her in all her glory.

Aboard the ship a fully immersive experience awaits, with no information boards or “interpretation panels” around at all. The idea is to explore and get lost, clamber into the bunks, nosily open whatever doors and trunks you like, wander into the Captain’s Office, you can even climb the rigging if you so desire.

The attention to detail is impressive, with all the sights and sounds you’d expect to hear if you boarded the ship 150 years ago. A worryingly authentic stench of vomit even emanates from a seasick passenger’s cabin! It was refreshing to experience the ship for yourself and not be told what’s what. I’m a big lover of reading everything I can wherever I am but it does often detract from the imaginative experience you need to really connect with a place like this. An absolutely amazing job done all round I’d say, I left feeling appropriately awe-inspired as you can probably tell. Despite having an aversion to revisiting attractions (preferring to discover new ones whenever I can) I’ll definitely come back to this one. I got so engrossed in the ss Great Britain’s story that I researched a lot more when I got home, I hope I’ll do her history and value justice here…

The attention to detail is impressive, with all the sights and sounds you’d expect to hear if you boarded the ship 150 years ago. A worryingly authentic stench of vomit even emanates from a seasick passenger’s cabin! It was refreshing to experience the ship for yourself and not be told what’s what. I’m a big lover of reading everything I can wherever I am but it does often detract from the imaginative experience you need to really connect with a place like this. An absolutely amazing job done all round I’d say, I left feeling appropriately awe-inspired as you can probably tell. Despite having an aversion to revisiting attractions (preferring to discover new ones whenever I can) I’ll definitely come back to this one. I got so engrossed in the ss Great Britain’s story that I researched a lot more when I got home, I hope I’ll do her history and value justice here…

The ss Great Britain was designed and built by the Great Western Steamship Company headed up by that top-hatted 19th century genius of industrial engineering, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. After the success of their first ship, the ss Great Western, which sailed to New York transporting trans-Atlantic passengers in style, Brunel wanted to build another ship that made even more of a splash in the luxury liner world. He set about building an iron boat, one of such size and power the world had never seen. The combined use of iron instead of wood and the installation of a screw propeller instead of traditional side paddles gave the ss Great Britain a pioneering advantage over every other ocean liner of its time. When it first “floated out” in 1843 it was by far the largest vessel on the seas, a revolutionary ship and the forerunner of all modern shipping. Sadly though the decision to be innovative and pioneering with her design and construction meant research and testing of the new methods were lengthy. Delays in the launch of the ship due to limitations of the narrow gates at the floating harbour in Bristol meant her journey to London for fit out was delayed for over a year. Finally when she began her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, 5 years overdue, her sailings were dogged with yet more problems. Expensive issues with the propeller redesign, excessive rolling, machinery wear, bad weather and finally some terrible navigational errors made by her captain saw ss Great Britain run aground at Dundrum Bay, Ireland in 1846, only a few trans-Atlantic crossings and just a year after her maiden voyage. At great expense she was finally floated free from the beach a year later in 1847, but the costs finally bankrupted the Great Western Steamship Company and the shareholders decided they could not finance the ship or the company any longer.

The ss Great Britain was designed and built by the Great Western Steamship Company headed up by that top-hatted 19th century genius of industrial engineering, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. After the success of their first ship, the ss Great Western, which sailed to New York transporting trans-Atlantic passengers in style, Brunel wanted to build another ship that made even more of a splash in the luxury liner world. He set about building an iron boat, one of such size and power the world had never seen. The combined use of iron instead of wood and the installation of a screw propeller instead of traditional side paddles gave the ss Great Britain a pioneering advantage over every other ocean liner of its time. When it first “floated out” in 1843 it was by far the largest vessel on the seas, a revolutionary ship and the forerunner of all modern shipping. Sadly though the decision to be innovative and pioneering with her design and construction meant research and testing of the new methods were lengthy. Delays in the launch of the ship due to limitations of the narrow gates at the floating harbour in Bristol meant her journey to London for fit out was delayed for over a year. Finally when she began her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, 5 years overdue, her sailings were dogged with yet more problems. Expensive issues with the propeller redesign, excessive rolling, machinery wear, bad weather and finally some terrible navigational errors made by her captain saw ss Great Britain run aground at Dundrum Bay, Ireland in 1846, only a few trans-Atlantic crossings and just a year after her maiden voyage. At great expense she was finally floated free from the beach a year later in 1847, but the costs finally bankrupted the Great Western Steamship Company and the shareholders decided they could not finance the ship or the company any longer.

The ship was bought for a mere £25,000 and refitted with major mechanical adjustments. She sailed one last time on the trans-Atlantic route before being sold on again to Anthony Gibbs and Sons who had seen the profit potential in transporting emigrants to Australia during the gold rush of 1851. Even after gold rush fever had died down the route remained popular and ss Great Britain sailed between Liverpool and Melbourne for over 30 years, transporting over 15,000 emigrants down under. She was by far the quickest and most reliable ship on the England Australia route and only ceased service in 1882. The mystery of her longest serving captain, John Gray, who disappeared without a trace during a sailing in 1872 after captaining the ship for 18 years has still never been solved (and it’s through this intriguing story that visitors are encouraged to explore the now restored ship).

She was sold again in 1882 and converted for use as a cargo ship carrying coal, but just 4 years later a fire broke out on board during a storm and when she reached the closest port in the Falkland Islands she was deemed too damaged to repair or ever sail again. She was sold for the last time to the Falkland Islands Company and used as a bulk storage hold. Eventually in 1937 she was declared unfit even for use as a storage vessel, when the owners approached the Royal Navy even they were purported to have turned her down as a target for torpedo exercises! Finally she was towed to Sparrow Cove, a few miles from Port Stanley in the Falklands and scuttled. Large holes were bored in her hull which sank her into the shallow waters and there she lay, abandoned for the next 30 years.

Now, it’s the final part of ss Great Britain’s story that gets me really excited. I watched the video of the ambitious rescue and her eventual homecoming twice in the discovery centre and have now predictably become fascinated with “scuttled” ships and shipwrecks. The BBC documentary made in 1970 is viewable here and it’s worth a watch to really understand the magnificent rescue. This photo shows the ss Great Britain in Sparrow Cove in the early 1960s, still with her masts intact (probably because the main mast was made by binding 4 great trees together!) and standing proud despite her 30 year abandonment to the sea and elements. The rescue mission was begun in 1968 when Dr Ewan Corlette, a marine architect who was passionate about the ss Great Britain, wrote a letter to the Times to garner support for a mission to bring her home. Brunel’s ship was of such significant historic importance and as time was running out to save her soon backers came forward to fund the project, including Jack Hayward. A working party was formed and a naval survey undertaken with the help of the Royal Navy to assess the feasibility of bringing her home. A huge crack was found in the hull, so bad that experts said she would have split in half within 6 months. By chance the actual dry dock she was built in was lying unused and derelict in Bristol since the area was damaged during bombing in WWII. After negotiations and painstaking planning it was finally agreed that she could be floated back to Bristol, a salvage of gigantic proportions.

Now, it’s the final part of ss Great Britain’s story that gets me really excited. I watched the video of the ambitious rescue and her eventual homecoming twice in the discovery centre and have now predictably become fascinated with “scuttled” ships and shipwrecks. The BBC documentary made in 1970 is viewable here and it’s worth a watch to really understand the magnificent rescue. This photo shows the ss Great Britain in Sparrow Cove in the early 1960s, still with her masts intact (probably because the main mast was made by binding 4 great trees together!) and standing proud despite her 30 year abandonment to the sea and elements. The rescue mission was begun in 1968 when Dr Ewan Corlette, a marine architect who was passionate about the ss Great Britain, wrote a letter to the Times to garner support for a mission to bring her home. Brunel’s ship was of such significant historic importance and as time was running out to save her soon backers came forward to fund the project, including Jack Hayward. A working party was formed and a naval survey undertaken with the help of the Royal Navy to assess the feasibility of bringing her home. A huge crack was found in the hull, so bad that experts said she would have split in half within 6 months. By chance the actual dry dock she was built in was lying unused and derelict in Bristol since the area was damaged during bombing in WWII. After negotiations and painstaking planning it was finally agreed that she could be floated back to Bristol, a salvage of gigantic proportions.

It wasn’t a decision taken lightly, many a wrecked ship has been lost during rescue or restoration efforts, many from around the Falklands where over 100 old shipwrecks still lie. Pictured left is The Lady Elizabeth, another 19th century hulk that ran aground in Whale Bone Cove in 1937, which now looks set to break up and decay completely despite plans to turn her into a museum ship during the 1980s. In 1967 the Finnish ship Fennia was towed away from Port Stanley in the Falklands where she was being used for wool storage. The plan was to restore her too as a museum ship in San Francisco but money ran out and she only got as far as Montevideo, where she languished until eventually she was towed to Uruguay and scrapped. It’s for this reason that many Falklanders oppose the removal of the wrecks, the shipwrecks form part of the Islands’ heritage and their presence there is a monument to the world’s naval history.

But the ss Great Britain was lucky and with some ingenious engineering she was floated onto a pontoon which was first submerged beneath her then pumped full of air to raise it. The break in her hull was filled with mattresses and closed as she rose, then she was patched up with wood sheeting. She began her 9000 mile trip back to Bristol on her pontoon being precariously towed across the oceans, finally reaching Bristol where 100,000 people lined the river bank to watch Brunel’s ship pass under Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge (I was weeping in the Discovery Centre during this bit of the video, obviously).

I’ve spent most of this week on wreck websites like The Wreck Site, watching survivor rescues of the modern replica of the Bounty which sank in 2012 and trying to fight the urge to book myself on the next MoD flight out of RAF Brize Norton to the Falkland Islands because I’ve become so fascinated with the ss Great Britain’s story! The desire to cross the seas and build ships to match the ferocity of the waves is nothing short of unbelievable to me. While we carry on with our modern lives, when we can take ships on the ocean and sail easily from one country to the next, we usually think nothing of the feats like the ss Great Britain that have gone before to make it all possible. The people involved in the amazing mission to rescue such an important ship and the work of all those who now present her as an engaging and inspiring museum ship frankly restore my faith in the human race, truly fantastic.